Irish Yeast in the Trade Unions

By L.A. O’Donnell

Irish immigrants escaping to the United States from famine and oppression in their native land came, not only to nourish their hunger, but also out of thirst for freedom and independence. Mostly poor, they filled the ranks of unskilled labor but quickly began organizing to protect their rights as workers and advance their wages and working conditions. From Terence Powderly of the Knights of Labor to George Meany of the AFL-CIO, Irish-Americans fought the good fight to secure their human rights and further the cause of social justice.

Irish-Americans in the labor movement did not forget the cause of independence for their native land either. In 1920 they campaigned successfully for a resolution at the AFL convention demanding independence for Ireland. As recently as 1981, the Pennsylvania AFL-CO expressed “vigorous support for the cause of freedom in Northern Ireland” in a resolution adopted at its convention.

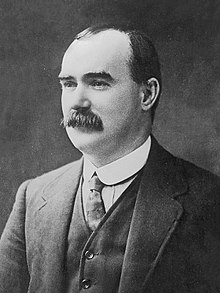

In Irish history, the movement for independence and the union movement were closely entwined. James Connolly and James Larkin were Ireland’s outstanding labor leaders as well as champions of Irish independence. Connolly was executed for his important role in the Easter Week Revolt of 1916. Larkin founded the Irish Transport and General Workers Union, largest in present day Ireland. Connolly collaborated with him in his efforts to get the union firmly established.

Both men were born in Irish ghettos outside Ireland. Connolly in Edinburgh, from which he escaped at age fourteen by joining the British army for seven years, Larkin in Liverpool from which he escaped by going to sea. Both of them were gifted organizers who put their talents to work on both sides of the Atlantic.

Each of them spent considerable time in the United States attempting to raise money and campaigning for labor organizations and other causes. They found most trade unionists in America a good deal less radical than they themselves were. Connolly came over for a four month speaking tour in 1902 at the invitation of the Socialist Labor Party. He returned a year later for a seven year stay.

During his stay in America, Connolly brought his family over and scrounged a bare living at various jobs including one at Singer Sewing Machine in Elizabeth, New Jersey. He was actively engaged in the Socialist Labor party until he tangled with its guiding genius, Daniel DeLeon, the “Socialist Pope”. At one time he worked for the IWW organizing longshoremen on the New York docks. His efforts were instrumental in the expulsion of DeLeon from the IWW. At the time he lived in the Bronx.

In the Bronx, the Connolly’s were neighbours and close friends of the Flynn family whose best known daughter was Elizabeth Gurley Flynn – then still a teenager, but soon to become a famous rouser and organizer for the Wobblies. At an outdoor rally on a warm summer evening in 1908, Connolly, the Flynn girl and her husband listened to a fiery old Irishwoman scold her audience for failing to help the Western miners in their strike.

The speaker was Mary Harris “Mother Jones.” Her tongue was so sharp, and she described the bloodshed and violence so vividly that Flynn – then pregnant – fainted. Connolly, luckily, caught her as she was about to fall. Mother Jones interrupted herself long enough to command “get that poor girl some water” and continued her scold. Jones was a United Mine Workers organizer and close friend to many labor leaders but particularly John Fitzpatrick, head of the Chicago Federation of Labor and Terence Powderley. Thereafter she took a maternal interest in James Connolly and Elizabeth Flynn, (a young trade union radical born in New York of Galway parents in 1890).

Returning to Dublin in 1910, Connolly became associated with James Larkin in establishing the Irish Transport and General Workers Union. In 1913 he was involved along with Larkin, in the great labor dispute of that year which reached its climax in the “Bloody Sunday Riot of August 31. The dispute dramatized the poverty, disease and overcrowding of slum dwellers in Dublin and convulsed the city entirely. Connolly assumed leadership of the Transport Workers Union when Larkin left for America in October of 1914, ostensibly for a short fundraising trip, but one that actually kept him out of Ireland for nine years – the last four of which were in Sing Sing prison serving a sentence for “criminal anarchy” until pardoned by New York Governor Al Smith.

When James Larkin arrived in New York in 1914, haggard and exhausted from the 1913 upheaval he immediately called upon the Flynn’s, announcing simply, “James Connolly sent me.” Thereafter, he was a frequent visitor to the Flynn household, delighting to drink tea with the family since he, like Connolly, was a teetotaller. But Larkin did much more than drink tea in the United States. Until 1919, James Larkin actively engaged in the work of the IWW, especially in its efforts to oppose World War 1. His socialism and his hatred for Ireland’s subjugation combined to make him a passionate opponent of the war. He was a thundering, explosive and unpredictable public speaker who could bring a crowd to its feet at will. He travelled all around the country demanding justice for the poor and an end to the war. For his efforts he was tried and imprisoned for “criminal anarchy.” Upon his return to Ireland in 1923 he discovered his union was in the hands of charismatic leaders who thwarted his attempt to resume leadership of it. He died in 1947.

In the course of the 1913 upheaval in Dublin, Larkin’s union organised a force to defend workers against police attacks. Though numbering only in the hundreds, it was called the Irish Citizen Army and Connolly’s experience in the British military was drawn upon to train it. Though small, the ICA played a significant role in the Easter Rising of 1916, making up much of the soldiery which occupied the General Post Office in Sackville Street (now O’Connell St). At the time Patrick Pearse, although proclaimed President of the Provisional Government and Commander in Chief, deferred to Connolly’s superior military knowledge and experience and permitted him to direct the operation. Connolly proved a decisive tactician but was able to hold out only one week before surrendering to the overwhelmingly superior numbers of British forces. In the action Connolly had sustained a bullet wound in the ankle which then grew gangrenous.

Leaders of the insurrection numbering over one hundred were methodically tried and sentenced to death for treason by the British. Connolly was the fifteenth to be executed in Kilmainham Prison (14th actually) after having been received back into the Catholic faith, shriven, given communion and last rights. His wife, Lillie and daughter Nora visited with him on the eve of his execution and found him calm, without illusions and resigned to his fate – perhaps anticipating release from a life of poverty and frustration. Seated on a box before the firing squad because of his wound, he met his death on Friday, May 12th 1916 and entered the pantheon of martyrs for Irish freedom.

Public opinion in Dublin and throughout Ireland had seriously mixed feelings about the uprising in view of the many Irish sons who had enlisted in the British army and the belief that the rising was conducted by a small number of radicals. When, however, English authorities began systematically executing its leaders – especially the wounded Connolly – the tide of opinion shifted dramatically, and momentum for independence became irresistible. Sobered by the response, the British halted all executions after Connolly’s. But it was too late.

Note: The late L.A. O’Donnell was professor of economics at Villanova University, USA and author of Irish Voice and Organized Labor. He wrote many articles on labor and economic history, emphasizing the contribution of Irish immigrants. He died in 2011.