Radio Telefis Eireann (RTE), the Irish public broadcaster has reported that recent Oscar winner Cillian Murphy from Cork will star in and produce the film adaptation of Mark Bradley’s book, ‘Blood Runs Coal: The Yablonski Murders and the Battle for the United Mine Workers of America. (UMWA)

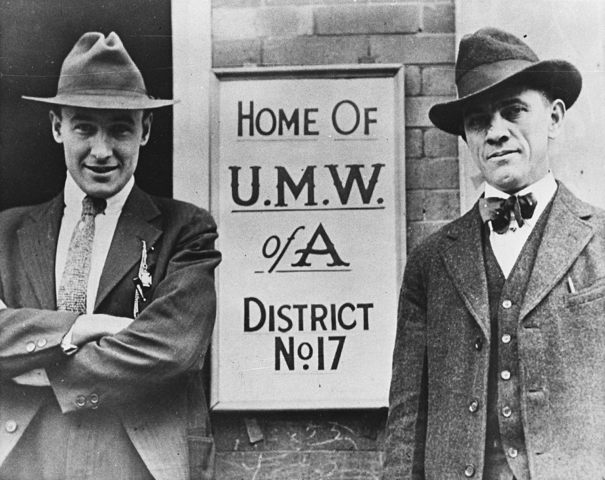

The report states that Murphy’s latest film project will concentrate on the terrible dark tale of corruption in the UMWA trade union in the 60s and early 70s under the leadership of Tony Boyle and the murder of the Yablonski family.

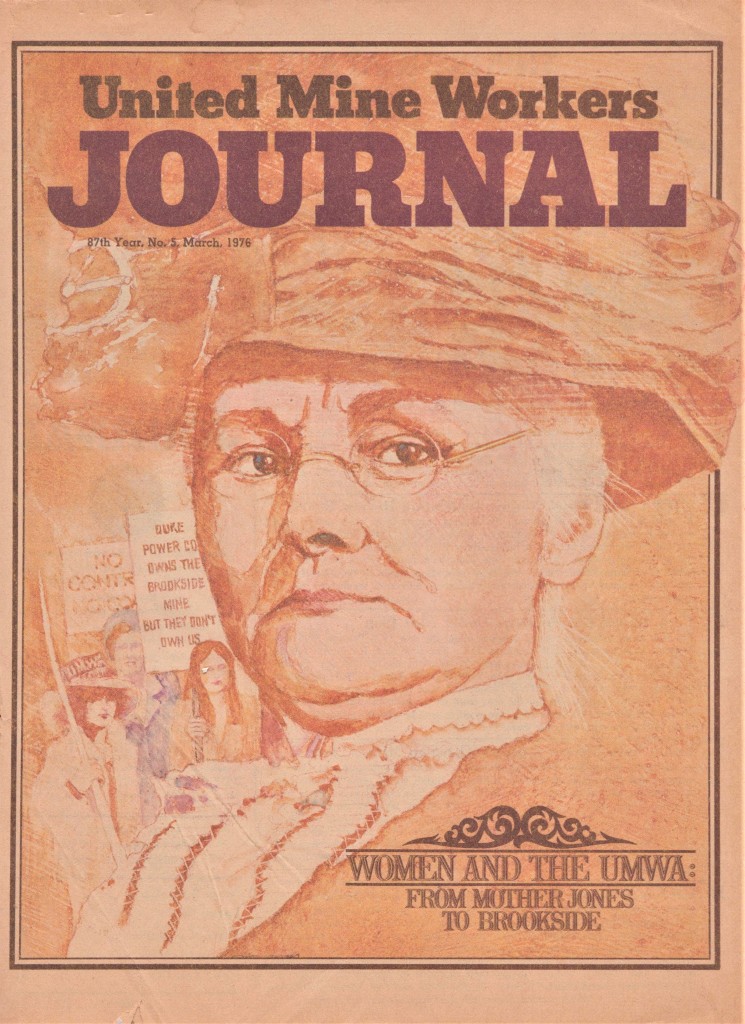

Yet during the long history of this great union, it has provided a beacon of hope and inspiration to hundreds of thousands of American union miners and their families over the past 130 years and had a unique Cork link in the connection with Mary Harris (Mother Jones), who was appointed the union’s first female organiser.

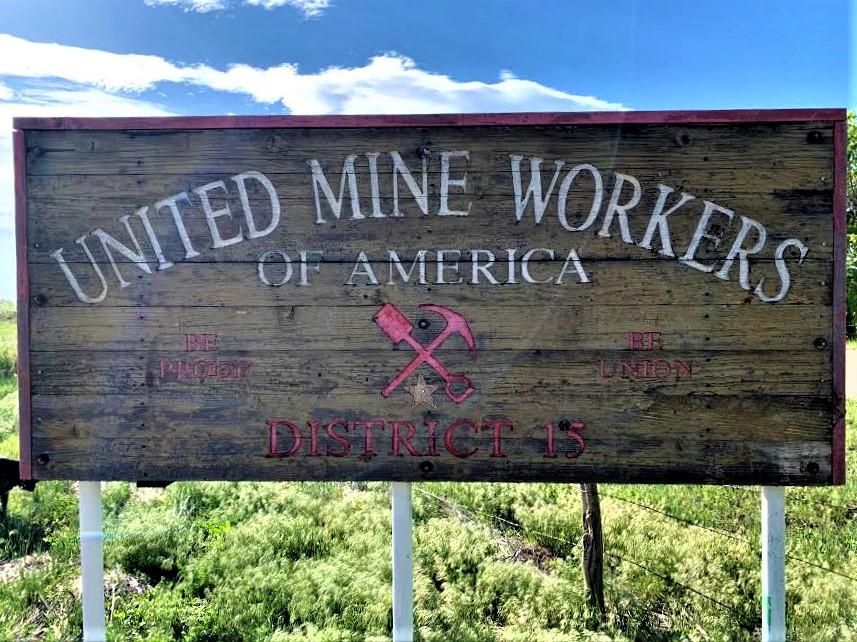

Founded in January 1890, the UMWA went on to become the largest, toughest and most powerful trade union in the history of the troubled American Industrial relations. Men such as Michael Moran, John McBride and Richard Davis along with thousands of miners forged the reputation of solidarity in this proud union.

Mary Harris was appointed a UMWA organiser in the late 1890s and from then until the early 1920s, she spent more time organising miners than any other group of workers. She became part of a large group of tough male union UMWA organisers, many of whom were Irish. Following the Lattimer Massacre in 1897 in which 19 miners were killed, John Mitchell, just twenty eight years old of Irish immigrant parents became the fifth president of the UMWA. He succeeded Michael Ratchford from Co Clare, who as president was the first to notice the organising ability of Mother Jones and hired her to become a UMWA “walking delegate”. John Mitchell later appointed her as a paid organiser in 1901 to try to unionise the difficult West Virginia coalfields.

Over the next decade, Mother Jones became the most active, colourful, and outstanding union organiser during a period of violent industrial unrest which saw the UMWA call several national coal strikes to seek decent wages, safe conditions and shorter working hours. Mother Jones was directly involved in numerous strikes from Pittsburg, to West Virginia, to Arnot in Pennsylvania, to Colorado where she unionised thousands of miners as the UMW grew into the strongest and most diverse union in America. Later Jones played an active part in the Coal Wars in West Virginia and Colorado from 1912-1914 in which dozens perished in the brutal pitched battles between the miners and militias along with private detective firms paid by the mine owners.

In July 1902, as a result of her union activities, Mother Jones was described in court as “the most dangerous woman in America.”. Later she fell out with President John Mitchell but each retained a great respect for each other. Today a large monument of John Mitchell stands in Scranton in Pennsylvania, the hometown of President Joe Biden. Very soon Mother Jones will have her own monument in the city of Chicago.

In recent years the UMWA union membership has been much reduced due to the decline of the mining industry but it is now actively organising among other workers including the public sector.

The current president of the UMW is Cecil Roberts, who is the great-grandson of Ma Blizzard.

Ma Blizzard was a fearless union activist in Cabin Creek, West Virginia, and a great personal friend of Mother Jones during the Coal Wars. Her son Bill Blizzard was a miners leader at the Battle of Blair Mountain in 1921.

President Roberts in a beautiful Proclamation, presented by James Goltz from Mt Olive, Illinois to the Cork Mother Jones Committee in 2014 expressed “special thanks and recognition to the remarkable annual Spirit of Mother Jones Festival for keeping her Irish Spirit alive in her birthplace in County Cork, Ireland, in the Shandon area of Cork City”.

Speaking about Mother Jones, the UMWA Proclamation continued,

“We loved her and still love her. We call her the Miners’ Angel. Only an angel could have endured all of the suffering, hate and obstacles that the industrial masters hurled at her as she valiantly fought for the dignity, economic security and safety for mine workers and their families.”

extract from the Proclamation to the Spirit of mother jones festival from cecil roberts, president of the umwa.

The connection of the UMWA to Cork continues as we look forward to Oscar winning actor, Cillian Murphy playing the part of Chip Yablonski as he seeks justice for his coal mining father.